Having a celebrity talk to you on social media is always a strange experience. I say always, but it’s literally only happened to me once. This month, actually.

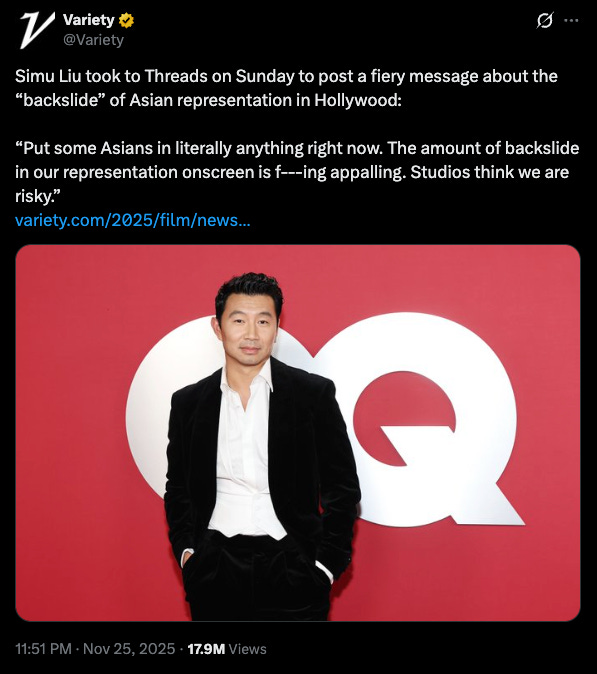

In November, I saw a post by Variety giving a quote from actor Simu Liu, the star of Marvel’s Shang Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings:

“Put some Asians in literally anything right now. The amount of backslide in our representation onscreen is f---ing appalling. Studios think we’re risky.”

My immediate reaction was an eye-roll.

I don’t like race-first advocacy. “We need more BLACK stories. We need more ASIAN stories!” Should I, a child of Oklahoma, demand more dustbowl redneck representation? If I did demand such a thing, you might rightly ask why those stories, specifically, must be told in greater numbers. Shouldn’t stories just be good, in all the variety that comes with quality?

I also just don’t like Simu Liu. Which is why I felt moved to make a bitchy tweet about him.

When I saw his complaint, I quote-tweeted Variety: “All I’m…