Scroll to the bottom for a video essay version of this article

This past weekend, I watched all seven episodes of the Netflix limited series, Midnight Mass. The show can reasonably be classified as a religious, supernatural thriller and was written by Mike Flanagan, who also brought us the Haunting of Hill House and The Haunting of Bly Manor. Like those shows (which I also enjoyed), Midnight Mass is about so much more than a mysterious new priest in town or the reasons behind seeming miracles. It is about faith, the dangers of zealotry, and the need to examine ourselves at the deepest levels.

If you intend to watch it, I recommend you do so before reading the rest of this, because I spoil the whole thing.

Midnight Mass takes place on a small New England island accessible only by a twice-daily ferry. After an oil spill that decimated the fishing industry in the area, the island has shrunk to a population of less than 200. It is run-down with an aging population. The few children on the island are just looking for a way out and the adults are worn down from decades of hard, physical work and financial woes. But they have their faith.

Nearly all the residents are Catholic, though only a few are devout enough to attend Mass every week. They've had the same priest for several decades.

But when the old man goes off to the Holy Land for a pilgrimage, another, younger priest comes back in his place. The Monsignor has taken ill, the younger priest says. And he, Father Paul, has been sent by the Archdiocese to stand in for him while he recovers.

Shortly after Father Paul arrives... the miracles begin.

A teen girl confined to a wheelchair walks to receive the sacrament

An elderly woman with dementia begins to recover memory and her physical ailments also improve

Father Paul himself dies of what appears to be poisoning...only to come back to life

These signs and wonders are observed by the tiny island and word spreads: God is with us on Crocker Island. Come and be faithful.

And they do. The whole island (except the Muslim sheriff, the Atheist prodigal son, and a few skeptical others) go to Mass every week. Their faith is restored, as are their bodies.

And it never occurs to them. None. Of. Them. That these signs and wonders might be coming from something other than God.

It is in this narrative backdrop that Mike Flanagan gives us a set of rules, or perhaps guidelines would be better to say, about how to live righteously. These rules are for everyone: The fervent Catholics crowding into Mass, the discouraged Atheist looking for redemption, and for everyone in between.

Groupthink Can Kill

There comes a point in the show where the mask is fully off Father Paul. He reveals completely that he is following his own will, his own desires, rather than God's. And he is using cherry-picked, out-of-context Bible passages to justify the horrendous things he has done and plans to do. At one point, he stands in front of a packed church giving a repulsive, blasphemous Good Friday homily, and I was overcome with supreme sadness.

The whole congregation, except one person, listened to that garbage... and nodded along. Because they had watched a young paralyzed girl walk. Because they no longer needed to wear their glasses or their back no longer ached. They saw the signs and wonders and they couldn't see anything else.

They attacked anyone who tried to point out "God doesn't work like this." They ignored their lifetime of sitting in Mass and listening to Jesus's words, his warnings, about false prophets. And they felt justified because the only people who rejected Father Paul were already outsiders, already misfits.

By the time anyone in the in-group realized how wrong they had been, it was far, far too late.

Do Not Presume to Stand in God's Place

Father Paul spends the majority of the show firmly in the wrong. Everything he does is so, so wrong. But he convinces himself that it is right. More than that, he convinces himself that God approves.

When he tells lies to the congregation about who he is, he asks God for forgiveness for the lies "he must tell in His service." When he kills a man, he says that his lack of guilt over it is proof that it is God's will. We watch both him and Beverly use scripture to justify the choices they have made instead of using it to guide them. And it is horrible to watch how assured he is.

In the end, he realizes what he's done. Too late. He put himself in God's place and justified it however he could because he was afraid. Of growing old and dying. Of missing out on a life he wanted but couldn't have. He was an old man looking back at his life and wishing it could have been different. There is an order to things. And he decided that it didn't apply to him. Too bad he wasn't alone in paying for that hubris.

Addiction (to anything) Changes Who You Are

The show starts with one of our protagonists, Riley Flynn, being sentenced to jail time for accidentally killing a girl while he was driving drunk. It is the guilt of this and his subsequent loss of faith that gives Riley such a clear view of what is happening in his home town. His addiction was alcohol, but the show goes much further in its condemnation of addiction than a simple matter of drunk driving.

In the last episode, when we discover what the "sacrament" really is and what it does, we have to watch in horror as good, decent people are overcome with a hunger they can't control. At the end, when reason once again returns, a young boy numbly tells a man, "I think I killed my mom." The man can do nothing but nod and comfort the boy, standing by him as they grapple with their lack of control and the horror it has wrought.

Power is the Strongest Drug of All

"You aren't a good person, Bev... God loves everyone else just as much as he loves you. Why does that bother you so much?"

The villain in this series is Beverly Keane (played by Samantha Sloyan). Not the supernatural menace in the shadows. It's Bev. This horrendous, power-mad woman was a "Karen" in the best of times, using scripture as a weapon to stand in judgment of everyone for everything. For what they wore, for how often they came to mass. For even daring to have a pet dog when she didn't decree him to deserve such a thing. We have all known a person like this.

They use some other authority to beat down those around them. In Bev's case, it was religion and her position as a church official. In other people's case, they invoke secular ideas like "common decency" or "public health." All with the idea that if you don't obey this person, then you are evil. And you deserve to be punished.

Giving someone power, even a little of it, is the truest test of character there is. And unfortunately, it seems the majority of people fail that test.

The final rule is only for Christians. But if you identify as one, listen up. And listen close.

The paradise Christ promised us comes in the next life. Not this one.

Anyone who tells you that if you are obedient enough, good enough, faithful enough, that you will be rewarded with riches and protection from tragedy... they are not of God. And they are selling you something.

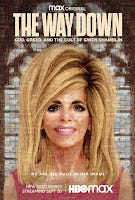

Just a week before I watched Midnight Mass, I watched The Way Down, a docu-series on HBO MAX detailing Gwen Shamblin and her Remnant Fellowship Church in Tennessee. If you saw it too, you probably noticed many similarities between the fictional Bev and the real-life Gwen. How they held themselves above others, how they felt empowered to decree who was worthy and who wasn't.

Ostensibly, the Remnant Fellowship Church is in the Church of Christ denomination. This is not one of those non-denominational churches that seems to make up their own rules. They have a firm (and strict) theology. So why did the majority of the congregants sit back and allow this? Why did so few leave? And the ones who did leave... it was only after they were ostracized within the church.

We saw the same thing in Midnight Mass. Though a fictional story, it tells us a nasty truth. We are willing to believe anything, as long as it comes from someone "on our side."

Even though we have been explicitly told about "the prophet, which shall presume to speak a word in my name, which I have not commanded him to speak" (Deut. 18:20), still we fail to remember what we've been taught.

Just give us something we want, show us something "miraculous," and it seems we fall like the walls of Jericho.

The power of a good story is that it makes us think. It helps us realize who we want to be. And who we were all along. So watch Midnight Mass and The Way Down. Watch the signs of deception, both real and fictional. And ask yourself, truly, if you would behave any differently. I so fervently hope that I would.

Good piece, I was just driven to distraction as a raised Catholic at your Midnight Mass summary that a barely attended New England parish would have a monsignor officiating 🤣